When I was in grade 3 and about 8 years old, we all had to do a drawing.

I chose some vivid colours to draw with – they were turquoise, yellow and black, and my efforts were highly praised. “What great colours you chose Cathy! You’re really good at this. Let’s show everyone your beautiful drawing.” I loved the attention of course, and lapped it up. I felt special.

The following week at art class we had to do another drawing, and so I did a version of the one I had done the week earlier. Same colours, similar design. I sat expectantly, waiting for the praise, but it didn’t come. I was crestfallen.

What was at play was the limitations of a fixed mindset, and how it is cultivated.

A fixed mindset (termed by Professor Carol Dweck) believes ability is innate and can’t be changed. You either have it, or you don’t. When I didn’t get the praise for doing something similar to what I was praised for previously, I believed that ‘I’m no good at art’.

With a fixed mindset, we go with what worked before, and we do things to avoid failure and criticism. If something doesn’t work out, we are more likely to give up, because it means something inherently lacking within us. There is no paradigm for improvement or change. Effort and hard work aren’t part of the picture – if you’ve had to work hard at something it means you’re not ‘a natural’.

Like in my drawing story, a fixed mindset can be cultivated through the wrong sort of praise. When you praise a child – or a colleague – for something they did (‘you’re really good at this Cathy), and not the process they went through (‘you really experimented with the colours Cathy’), you are enabling a fixed mindset.

This is because when you praise the person, you are suggesting that their success is due to fixed traits that they possess. These can’t be changed or improved – you’re ‘gifted’ in this particular area. When you praise the process, you are implying that their achievement is a result of the effort and thinking they put in. This gives them access to growth and improvement. More is possible.

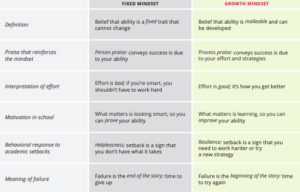

I think this table by Allison Master from the Mindset Scholars Network* is really helpful to distinguish your fixed mindset. It’s written for an educational context, but it works for any situation. Check the middle column for how you might relate to failure and setback, or when something doesn’t immediately work out for you. The reframe in the far column is a good way to question and change the belief you have.

For myself, I know that when I feel something isn’t working, and I feel dejected, the first place I check in my mindset. And I coach my clients on this too. For some people, there is a bias toward having a fixed mindset, so questioning it regularly is a smart way to evolve the beliefs that will move you forward.

This is true for us in large organisations, or even as Earthlings. When issues seem daunting, it can feel too easy to fall into a fixed mindset and give up. ‘We tried a change program but it didn’t work,’ or “It’s too late”, or “humans have made a huge mess and it can’t be fixed’ – are all indicators of not the truth – but a fixed mindset. No progress toward a solution is possible without addressing it.

I write to you a lot about mindsets because I believe we need to be radically awake to what’s driving our behaviour and our responses to difficult situations. When things are tough and not going to plan, it’s natural for us to want to ‘pick up our bat and ball and go home.’ But this is not appropriate to the challenges we face, nor is it enlivening and honouring of our potential as a species. Developing the type of expansive mindset that can hold the difficulties, but not be disabled by them, takes courage and leadership. I am my own work in progress about this, and I am here for that for you too.

* Allison Master’s article here is really great for more on how to cultivate the right sort of praise.